Urban Heat Island Effect

- ColumbusNDC

- Sep 21, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 29, 2021

As the climate warms, many aspects of urban life are beginning to change, and one growing problem is the urban heat island effect. Exacerbated by both the proliferation of hardscape surfaces that absorb solar heat and rising global temperatures, the heat island effect raises the temperature in cities and urban neighborhoods. Urban design features such as road pavement, parking lots, and building roofs become hot during the day when exposed to the sun. Without adequate vegetative ground cover or tree canopies, these hard surfaces create excess heat that can raise the temperature of the surrounding areas.

This temperature increase particularly impacts low-income neighborhoods, which are more likely to have less tree canopy coverage/green space and more heat-absorbing pavement than wealthier areas, and are often located near industrial areas that create heat.

This means that low-income urban neighborhoods can potentially be several degrees warmer than leafy suburbs outside of the urban core. Solutions to reduce the urban heat island effect include installing green roofs, increasing tree canopy and vegetation, and even painting roofs white in order to reflect sunlight rather than absorb it.

An illustration of the urban heat island effect, where the densest parts of the city experience the highest temperatures.

The heat island effect illustrates the inequity faced by low-income, inner city residents, where the effect is strongest. Typically tree canopies are far more robust in wealthier areas and suburbs than in low-income urban neighborhoods, which exacerbates the heat effect.

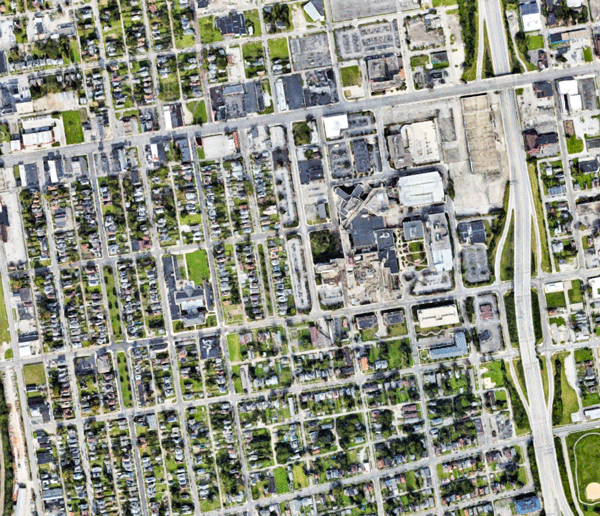

An affluent area of Central Clintonville has significant mature tree coverage, while a low-income area of Franklinton shows much more hardscaped surfaces and less greenery.

This is especially problematic considering low-income residents are more likely live in housing without air conditioning or proper ventilation and have higher rates of asthma. These smaller neighborhood-level heat islands are called “intra-urban,” where certain parts of a city are hotter than others because of differences in heat-absorbing pavements and buildings and the prevalence of greenery.

Brian Stone Jr., director of the Urban Climate Lab at Georgia Tech, feeling hot concrete. Pavement absorbs heat, which is why cities, he says, typically heat up at twice as fast as surrounding areas.

This disparity in temperature, and subsequently in quality of life, led to the creation of the term heat equity. Some cities have taken steps to address heat equity with policies and practices specifically targeting heat islands in order to mitigate them and assist people in adapting to their impacts. In addition to physical differences, there are also other connections between these intra-urban heat islands and the demographics of residents. For instance, those most at risk from heat-related health issues are the elderly and children, outdoor workers, people with pre-existing conditions. Many of these individuals are often concentrated in low-income areas that are also intra-urban heat islands

This diagram shows that the biggest daytime surface temperature spikes occur in industrial, urban residential, and downtown areas, despite only small fluctuations in actual air temperature.

High temperatures can exacerbate health problems such as asthma, already prevalent in low-income communities and becomes even more dangerous in urban areas.

The negative impacts of intra-urban heat islands further contribute to the inequalities between low-income and high-income areas. Residents in low-income areas are also more likely to work outdoor jobs that subject them to the heat, such as construction or landscaping, which further increases their vulnerability.

An example of a green roof, which is one effective mitigation strategy for the heat island effect.

Because the urban heat island effect is so connected to climate, it could worsen as temperatures rise. Cooling strategies to alleviate the heat island effect also help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as planting trees, adding green roofs or cool pavements, and smart growth that preserves nature, limits sprawl, and lessens the need for car travel. Mitigating the urban heat island effect not only protects the health of those it impacts, but also the environment.